While it is unlikely that anyone reading this is unaware of the general push to reduce carbon emissions as a means to limit our potential impact on climate change, the ever-evolving lexicon of emission reduction metrics, schemes, and governing bodies can be confusing. I would hardly recommend that a network infrastructure professional dedicate the requisite years of constant study to become a subject-matter expert on every backstreet and alleyway of the greenhouse gas challenge, but there are some topics that have proven to have staying power in the commercial space and are worth getting your arms around.

Chief among these emission reduction initiatives is the Greenhouse Gas Protocol, more commonly referred to as the GHG Protocol. The GHG Protocol had its start back in the late 1990s, when two major NGOs, the World Resources Institute and the World Business Council for Sustainable Development, set out to standardize corporate GHG accounting and reporting metrics. With help from major global corporate partners, they developed a “global standardized framework to measure and manage greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from private and public sector operations, value chains and mitigation actions” (GHG Protocol Website), the first edition of which launched in 2001.

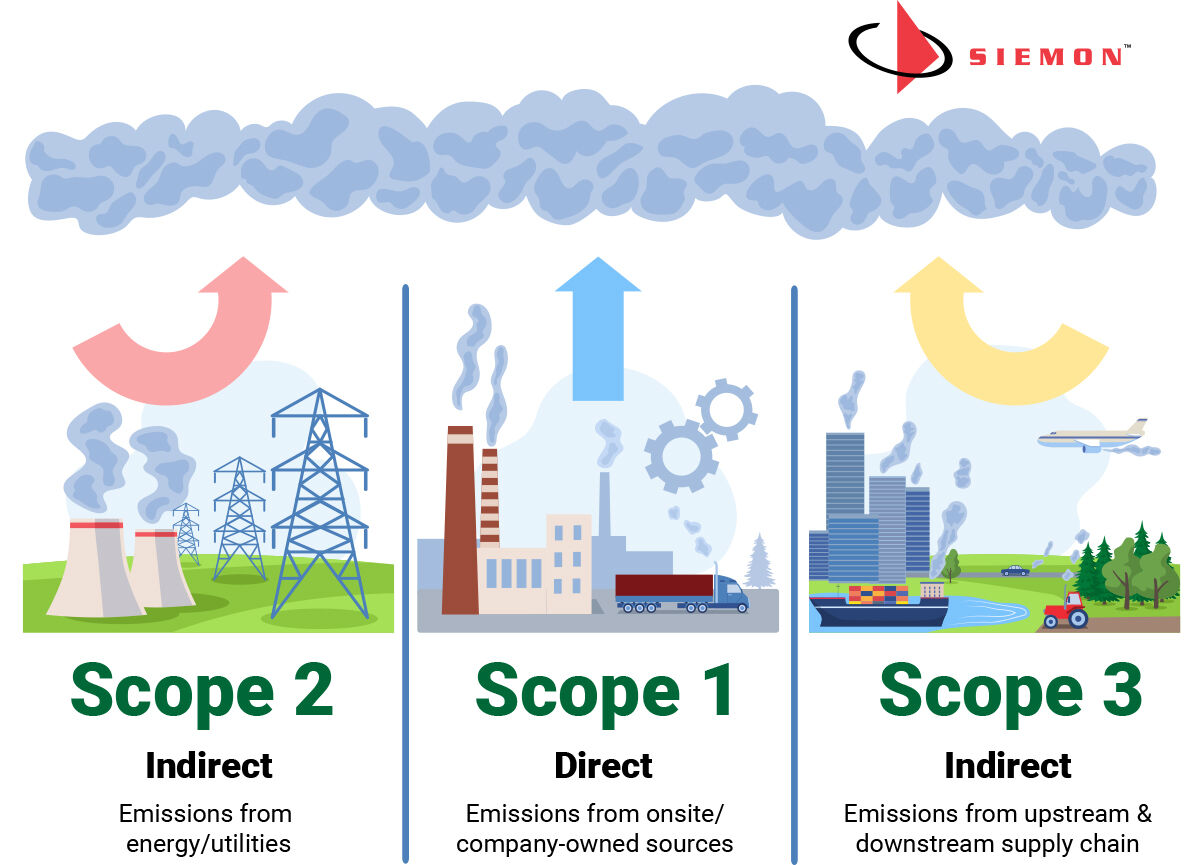

Today, the GHG Protocol is the key global standard for quantifying GHG emissions, and it categorizes a given organization’s emissions by “Scopes.” If you haven’t heard or seen carbon emissions broken down by Scope 1, Scope 2, and Scope 3, you certainly will soon enough, and our purpose here is to clarify what it all means.

Scope 1

The emissions are those generated directly by activities taking place at company owned or controlled locations. We’re talking about the use of fossil fuels for heating, the escape of industrial fumes in manufacturing processes, and company-owned fleet vehicles. The key word here is “direct” – Scope 1 emissions are the direct result of activities at company locations.

Scope 2

This scope is even easier to understand than Scope 1. Scope 2 covers the indirect emissions resulting from a company’s purchased energy. Although it can cover a few different energy sources, it is best understood as emissions from a company’s use of electricity. According to the GHG Protocol, Scope 2 represents more than a third of all global CO2 emissions, so it is a major area of focus in any credible reduction effort.

Let’s take a quick pause before jumping into Scope 3. Many, if not most, companies that publicly report on their GHG emissions focus on Scope 1 and Scope 2 only. This is an understandable boundary for most organizations to set. The required Scope 1 and Scope 2 input data is largely gleaned from internal sources like electricity and fuel bills and there are many publicly available, GHG Protocol-blessed tools for converting raw consumption data into GHG emission equivalents. Scope 3 takes a good deal more effort. This is not to say that there’s anything wrong with organizations who stick to Scope 1 and Scope 2 (in fact, any company accurately reporting on their carbon footprint according to GHG Protocol standards is taking a very meaningful step in the right environmental direction), but reporting on Scope 3 is a whole new ball of wax.

Scope 3

The real challenge differentiating Scope 3 from Scopes 1 and 2 is that it extends the GHG accounting boundaries beyond the direct control of the reporting company and out into its entire upstream and downstream value chain.

That means including the emissions resulting from the upstream extraction, production, and transport of the raw materials, components, and capital equipment a company purchases to “make” their product or service. Using Siemon as an example – for us to accurately track our Scope 3 emissions on a product like our Z-MAX outlet, we need to calculate the emissions generated by our suppliers during the production of the resins we use to mold the housings, the extraction and refinement of the copper we use in the contacts, the automated assembly machines we purchase, etc. This requires a company to hold its suppliers accountable to track and report on their own CO2 inventories – which is a very tough ask, especially for a large manufacturer.

And that is only half of the Scope 3 challenge. Companies also need to track and account for downstream emissions resulting from the transport, storage, lifetime energy use, and end-of-life processing of their product. Again, using Siemon’s Z-MAX as an example, we need to track the emissions resulting from shipping a connector to one of our valued stocking distributors, the energy and resources they consume to store and redistribute the connector to the end customer, the energy the product uses during its 20+ year lifecycle, and even the impact of scrap reclamation when the connector is removed from service.

As such, a company tracking emissions at the Scope 3 level is making a huge commitment to drive sustainability through their entire value chain (particularly in the manufacturing space, where Scope 3 emissions can easily dwarf Scope 1 and Scope 2). It is a combination of faith in suppliers and partners to hold their end of the bargain and the determination take action to ensure that it happens, based on the understanding that to meet global carbon reduction goals, everyone needs to be rowing in the same direction.

Ultimately, that is the brilliance of the GHG Protocol scheme. For a company to reduce their own full-scope emissions, they need the support of everyone on the value chain. It is a “rising tide floats all boats” approach that is hard to envision failing to drive positive change.

The bottom line

So as a network pro, here’s what you should come away with. In the short term, you can look into your suppliers’ and partners’ carbon accounting efforts. If they’re not reporting at all, ask them why not. If they’re reporting to Scope 1 and Scope 2, give them a pat on the back and tell them to keep up the good work. If they’re extending their boundaries to Scope 3, understand that they are truly devoted to building a more sustainable world. They’re in it for the long-haul and are committed to adapting their business model to drive sustainable growth for themselves and their partners – and you may want to start thinking about how you’ll answer if they ask you to provide data on your CO2 footprint.